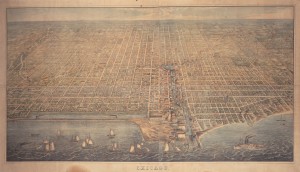

Our header image was cropped from J. T. Palmatary’s 1857 bird’s-eye view of Chicago. The full image is shown below (click on it for a full-size view); its publication details and the story behind the scene it depicts, as taken from Chicago in Maps by Robert A. Holland (New York: Rizzoli, 2004, pp. 80-83), follow below.

The Illinois Central Railroad

The Palmatary View

Title: Bird’s-Eye View of Chicago

Date Issued: 1857

Cartographer: J. T. Palmatary

Published: Braunhold & Sonne (Chicago)

Lithograph, 115 x 207 cm

Chicago Historical Society, ICHi-05656

Chicago’s new railroads greatly altered the city’s landscape. Wherever tracks were run—and they were run wherever the railroads desired—land use was immediately affected: depots and train yards dominated their surrounding neighborhoods, and commercial and industrial development quickly gravitated toward rail lines. Chicago literally grew up around its railroad tracks—it had to, as the railroads left only a single square mile in the center of the city free of their direct presence.

No railroad had a bigger impact on Chicago’s physical environment than the Illinois Central. The “IC” was long a dream of Senator Stephen A. Douglas; he had campaigned in 1846 on a platform that called for the federal government to cede public lands to the state for the purpose creating a railroad that would run the length of the state and extend all the way south to the Gulf of Mexico. Douglas had a nationalistic vision in which the railroads served to bind different sections of the country together: future railways would tie the West to the East; the Illinois Central would link the North with the South, ending the South’s growing desire for secession from the Union.

The IC was exceptional in two respects: it was a north-south railroad, and it was the first land-grant railroad. The railroad’s land grant was approved by Congress in 1850, largely due to the efforts of three men: Douglas in the Senate, “Long John” Wentworth in the House of Representatives, and the publicist John Stephen Wright. At his own expense, Wright had 6000 circulars printed and distributed, each bearing a petition to Congress to pass the “Douglas” plan; when the bill was about to come to the floor, Wright moved to Washington to personally lobby for it. The argument used to justify the grant was that the potential farmland of central Illinois would be inaccessible, and therefore without value, in the absence of such a railroad. As championed by Senator Henry Clay, the line of reasoning was that “by constructing this road through the prairie . . . you bring millions of acres of land immediately into the market which will otherwise remain . . . entirely unsalable.”

Just as had been done with the Illinois and Michigan Canal, the railroad was to sell the lands granted to it, using the proceeds for construction. The Illinois Central Railroad Company was established by the Illinois State Legislature in 1851, and in 1856, the 705-mile railroad—the longest in the world—began regular service from Chicago to Cairo. The railway soon became known as “the St. Louis cutoff,” as trade that previously had gone downriver to St. Louis now went to Chicago. In advertising and selling the two and one-half million acres of land along its route, the IC was a catalyst for growth in the central and southern regions of Illinois, attracting thousands of settlers and laying the foundations for agricultural, industrial, and urban development. This, in turn, provided the Illinois Central with its own economic lifeline, as these same settlers offered up their bounty for the railway to forward to Chicago.

The IC’s entry into Chicago was to set off a battle that would not be resolved for nearly half a century. In 1836, the Illinois and Michigan Canal Commission, which was responsible for the original sale of lots in Chicago, had seen fit to set aside one parcel of land along the lakefront for public use. Indeed, their real estate map marked the lakefront with the words “Public Ground—A Common to Remain Forever Open, Clear, Free of Any Buildings, or Other Obstruction Whatever.” This provision had distinguished Chicago from almost every other waterfront city in America, where the choice land along the water’s edge was typically appropriated by manufacturing and transportation concerns. These industries would soon develop into a wall of unsightly buildings and grounds, foul the water with their waste and runoff, and cut a city off from what was once its most picturesque feature. By 1850, this was the fate of Chicago’s riverfront; the lake, however, had thus far remained free of development.

The Illinois Central had originally wanted to enter the city to the west, where it would have direct access to Chicago’s industrial district. It was unable to follow this route, however, because the land it would need had already been bought by the Chicago & Rock Island Railroad. After purchasing land from Senator Douglas in the Lake Calumet area directly south of the city, the railroad’s directors requested access to Chicago’s inner harbor on a line directly along the lakefront. After months of bitter haggling, a compromise was reached. The City Council would permit the railroad’s trains to enter by way of a strip of land not on the lakeshore, but several hundred feet out into the lake. This would require the railroad’s tracks to be laid on trestles, which the railroad would have to protect from the lake waters by building breakwaters and dikes. This, in turn, would solve a civic problem that plagued the city for years: the flooding of the lakefront that was eroding away the canal commissioner’s Lakefront Park, and often sent water right to the front doors of the princely houses that fronted the park and lakefront along Michigan Avenue.

For its northern terminus, the Illinois Central had purchased part of the old Fort Dearborn reservation as well as some land along the river. As seen in the lithograph here, trains approached on a trestle erected in the water from Twenty-Second Street to the Randolph Street Depot. The area between the seawall and the shore created a basin that city officials tried to get the railroad to fill in, so that the city could create a new park and promenade. When the railroad rejected this idea, Chicago’s residents began to use the basin for swimming, sailing, and rowing. When, however, the railroad received court permission to create a landfill extension of its terminal, dock and storage facilities, the basin became landlocked and “turned into a still pool filled with industrial debris, floating packing crates, and the bloated corpses of horses and cattle.”

This striking 1858 view of the city clearly depicts the Illinois Central’s tracks (along with trains) on the lakefront breakwater. Note the basin between the lakeshore and the breakwater. The tracks can be seen leading to the Illinois Central’s terminal and branching out to warehouses at the mouth of the river. Individual buildings are clearly depicted along the city’s grid, and the river is lined with warehouses for the storage of grain and lumber. The downtown area lies left (south) of the river, the North Side neighborhood of old settlers to the right. The patch of lakefront just north of the river was a disreputable area known as “the Sands,” which became one of the major points of refuge from Chicago’s Great Fire.